|

||||

La Prensa

|

||||

|

English |

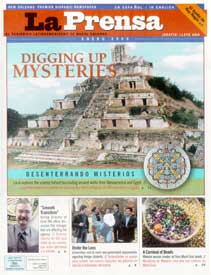

Digging up Mysteries

SCIENCE CREATED ART:

A NEW WAY

TO INTERPRET ANCIENT WORK

By Katherine Hart

It began with the Aztecs. Charles William Johnson was a sociology professor at the National University of Mexico when he noticed similarities between the Aztec calendar and pyramids.

"What blew my mind in looking at the pyramids and looking at the Aztec Calendar is that the proportion are the same," recalls Johnson. The round calendar and the Aztec’s huge pyramidal buildings, he found, share the same geometric patterns. That was 10 years ago. Johnson knows the exact date, for it was the beginning of an intellectual odyssey.

Leaving his 22 years academic career and his home in Mexico behind, he returned to his hometown of New Orleans. Continuing the work he starred in Mexico, he has produced volumes of analysis relating to the artwork created several millennia ago. His work has crossed not only time but continents and has delved into every field of study from linguistics to chemistry and physics.

Johnson, who has degrees in Latin American Studies and Oriental studies from Mexican universities, has been exploring the possible reckoning systems developed by the Mesoamericans and the ancient Egyptians. Proving the mathematical foundations of early artwork will help uncover the geometric relationships within de artwork, he says.

"What I’m doing is digging up the design behind the design," says Johnson, sitting on a couch in his book-cluttered Harahan apartment. "My thesis is that the designs came about because of math and geometry."

He maintains two websites that receive about 1,500 hits a day. With a new site launch in February, he plans to begin publishing his analysis of the geometry behind the ancient artwork.

Johnson has waited 10 years to make public his original theories on the geometry of the ancients, time he has spent exploring how the past cultures reckoned time and space. Throughout his work, he has tried to search as deeply as possible into how they made sense of the world around them. "I didn’t want to put words in their mouths," he says.

The mysterious culture of the Mesoamericans has fascinated scholars and casual observers alike. When archaeologists and others study the buildings, hieroglyphics and artifacts that these people left behind, they also search for explanations of what Mesoamericans believed and how they lived.

Johnson says he tries to avoid imposing his own interpretation on the Aztec, Maya and other cultures. The danger, he says, is in interpreting early cultures in terms of contemporary knowledge and values.

"We need to look at them in a different light and see what they want to tell us, not what we want to see," he says. "We need to stop looking at the past as something devoted form us. We came from them. We came from people who were very knowledgeable."

Some admirers of the Mesoamericans speculate that they were on a higher spiritual plane, Johnson says, while others see them as primitive. He himself views the ancients simply as smart people who knew their math and enjoyed creating complex puzzles.

Johnson is a self-taught mathematician. Half-Mexican on his mother’s side, he began college in Mexico when he was a teenager. While visiting relatives there, he received a scholarship. He stayed and spent the next three decades in Mexican universities.

Until 1993, he worked as a researcher at the National University of Mexico’s Institute of Social Research and taught sociology in the same university’s School of Social and Political Science.

In New Orleans, he works as a bilingual interpreter and translator and does clerical work that, he says, leaves his mind free to think. Mostly, he pursues his study of the logic of numbers and ancient reckoning systems.

The mathematical formulas he has uncovered relate to the forces of nature. The movement of the sun, for example, is reflected in the choice and pattern of numbers, according to his writings.

He has also found links between the Mesoamericans and ancient Egyptians, not just in the pyramidal structures but in the underlying math and in the languages they spoke. In some cases, the languages had similar words to express the same thoughts. The Maya called a storm kakh, while the Egyptians called it kkakha-t, for example. And both used the 360-day calendar.

"In my mind, there is no way the interconnectedness of all these numbers is by chance. The Egyptian numbers fit perfectly into the Maya system," he says. He does not offer an explanation for the similarities, except that there must have been communication between the two cultures.

Ancient artwork had multiple meanings, he surmises. The center of the Aztec Calendar may represent a religious symbol, a geometric form, a mathematical equation and artistic expression. "It is as though the ancient artwork was designed as computer microchips, storing infinite amounts of data," he says.

Johnson details his theories on his two Websites. One (www.earthmatrix.com) contains his essays on the mathematical basis of the geometric designs in ancient artwork. The other (www.the-periodic-table.com) covers another aspect of his studies: a new periodic table of the chemical elements that derives from his work on the Maya culture.

His table, based on the ancient system of reckoning, is getting some attention from the scientific community. Following his studies of past numbering systems, Johnson took the periodic table, which has been in use for some 130 years and which arranges the chemical elements according to their atomic number, and reconceptualized it into what he calls schemata.

"The [traditional] periodic table always bothered me," he says. "I would look at it and wonder, why not have a sequential numbering system?"

He applied the Maya counting method to the traditional periodic table and found it was relevant to the progression of elements. Then he color coded the images to reveal the patterns among the elements.

"Many new patterns and subpatterns of symmetry are being revealed for the first time," writes the editor of the scientific journal BELS Letter, Ann Morcos, about table. "For example, the placement of elements 71 and 103 are clarified with the schemata. This is a significant advancement in knowledge; however, it is small when compared with the numerous other relationships the schemata reveal."

For the past two years, Johnson has presented his findings at the national meeting of analytical chemists, called Pittcon, and he has been invited back to speak this spring in Orlando.

The Internet, however, is the primary vehicle for his work. He has not published in academic journals. His work, he notes, crosses the traditional barriers between academic disciplines.

Johnson’s research has led him to believe such limits are artificial. "What we can learn from this," he says, "is that we are all one, that everything is related."